You’ve probably spent hours re-reading textbooks and highlighting notes. Turns out, that’s one of the least effective ways to learn. Active recall is the opposite—and it actually works.

Here’s an uncomfortable truth about studying: re-reading your notes and highlighting textbooks feel productive, but they’re among the lowest-utility methods available. Your brain isn’t actually learning. It’s just pretending to learn.

Active recall, on the other hand, consistently ranks as the highest-utility study technique. It’s been proven across dozens of research studies to significantly improve exam performance and long-term retention. And it’s far simpler than you might think.

What Is Active Recall, Really?

Active recall is forcing your brain to retrieve information from memory rather than passively reading it. Instead of reviewing notes, you test yourself. You quiz yourself. You force your brain to pull information out of memory with no cues or hints.

Practical Example

Instead of re-reading a chapter on photosynthesis, you close your textbook and write everything you remember about how plants use sunlight to create energy. Then you check your work against the textbook and discover what you missed. That’s active recall.

The key mechanism is something researchers call the Testing Effect. When you test yourself, your brain treats the retrieval attempt as important. Even if you get it wrong, the act of trying to retrieve the information strengthens your memory of it. Your brain moves information from short-term working memory into long-term storage much more effectively through retrieval attempts than through passive review.

Why Your Brain Responds to This

Passive learning (reading, highlighting, reviewing notes) doesn’t engage your memory retrieval system. You’re just transferring information from a page into your eyes and maybe your working memory. There’s no effort involved, so your brain doesn’t prioritize storing this information.

Active recall is different. When you force yourself to retrieve information, your brain has to work. It has to search memory. It has to construct an answer. This cognitive effort signals to your brain that this information is important and worth storing in long-term memory.

There’s also an immediate benefit: active recall makes you aware of what you don’t know. When you re-read notes, everything looks familiar and you feel confident. When you test yourself, gaps in your knowledge become obvious immediately. You know exactly what needs more review.

How to Actually Use Active Recall

There are multiple ways to implement active recall, and they all work well:

Flashcards

Write a question on one side and the answer on the other. Test yourself by reading the question first and recalling the answer before flipping the card. Digital flashcard apps automate the spacing and scheduling, making this even more effective. Popular apps: Anki, Quizlet

Practice Testing

After learning material, take practice tests or quiz yourself using questions you create or find online. The struggle to retrieve answers is what creates learning, not getting them all right.

The Blank Page Technique

Pick a topic you studied. Get a blank piece of paper and write everything you remember about it. No notes. No references. Just pull it from your brain. Then check your work against your materials and identify gaps.

Study Groups

When you have to explain something to someone else, you’re retrieving and organizing information. When someone else teaches you, you can quiz them and force active recall on their end too.

Self-Explanation During Reading

As you read or learn something new, stop periodically and explain to yourself (or out loud) what you just learned in your own words. This forces retrieval and encoding simultaneously.

Combining Active Recall With Other Methods

Active recall is powerful on its own, but it becomes unstoppable when combined with other evidence-based techniques.

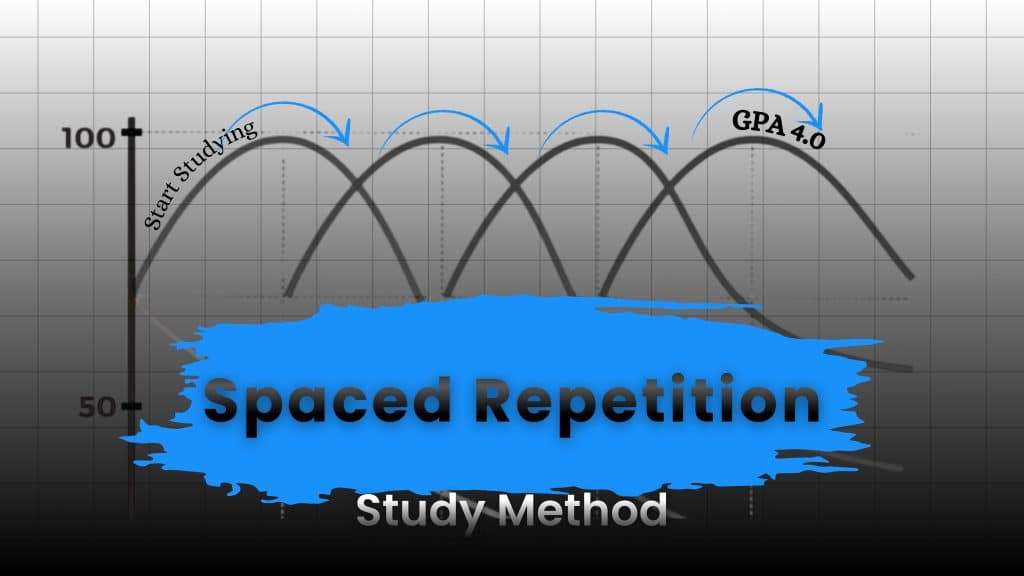

Pair with Spaced Repetition: Test yourself, then re-test yourself at increasing intervals (1 day, 3 days, 7 days, 21 days). This combines the power of retrieval practice with the brain’s natural learning timeline.

Use with Elaboration: When you test yourself and get something wrong, don’t just memorize the right answer. Elaborate on why the answer is correct. Explain the reasoning. Connect it to other knowledge you have. This deeper processing creates stronger, more flexible memory.

Add Interleaving: Instead of testing yourself on Chapter 1 thoroughly, then Chapter 2, mix questions from different chapters and topics during the same study session. This forces your brain to discriminate between concepts.

The Psychology of Active Recall

Part of what makes active recall so effective is that it’s harder than passive review. Because it requires more effort, your brain perceives the information as important and worth storing. This extra effort is literally the mechanism that creates learning.

But there’s a psychological trap: easier-feeling study methods often feel more productive even though they’re less effective. Highlighting feels productive. You’re making marks, you’re being active. Re-reading feels productive because material looks familiar. But neither creates strong memories.

Active recall often feels harder because you’re actually struggling to retrieve information. This struggle feels uncomfortable compared to the ease of re-reading. But the discomfort is a sign the learning is happening. This is why effective studying often feels less productive than ineffective studying.

Real-World Results

The research on active recall is overwhelming. Students who use active recall consistently outperform students who use passive techniques by ~13% on exams. When active recall is combined with spaced repetition, the results are even more dramatic. Medical students, law students, and other high-performing student groups commonly use these techniques together.

Try it yourself. Study for one test using your normal methods. Study for another using active recall. The difference will be obvious.

Getting Started Today

Start with one class or subject. Create flashcards for the key concepts. Test yourself daily. Add spaced repetition by scheduling reviews at increasing intervals. After one exam, you’ll see the difference.

The beauty of active recall is that it’s not complicated. It doesn’t require special materials or expensive tools. It just requires forcing your brain to retrieve information instead of passively reading it. Your brain responds, and learning happens.